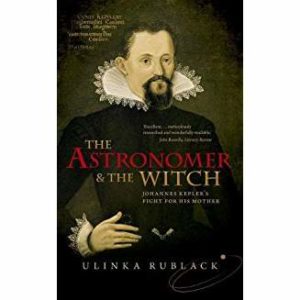

Ulinka Rublack looks back at the life of Johannes Kepler and the year he spent defending his mother against charges of witchcraft in their hometown of Leonberg, Germany in the early 17th century in her engrossing book, The Astronomer and the Witch.

Kepler’s work fits neatly into a time when there was great excitement in studying the natural world, which was seen as part of God’s great plan. There was enthusiasm for mechanical developments such as clocks, as well as natural remedies. While women were generally not educated, they nevertheless had access to medicinal plants and herbs, and Katherina Kepler used these for herself, family and friends.

Kepler was around 50 in 1720, when his mother was arrested and imprisoned. He had previously been associated with Tycho Brahe and Emperor Rudolph II and had already published many of his most important works, but experienced career ups and downs in a time of great instability between Catholics and Lutherans. We learn something about his personal life and relationships with colleagues, family and friends.

Leonberg and its neighboring towns regularly prosecuted witches, who were often older women, hanging or burning those convicted. Katharina’s initial accuser gained support, and rumors turned to testimony against her. Her tough, confrontational manner hurt her case, with a biased and corrupt local official complicating things. Over 70 at the time of the arrest, she’d been a widow who’d raised a family on her own and successfully supported herself for over 30 years. She was jailed for over a year while chained to the floor.

At the same time Kepler published his Epitome of Copernican Astronomy, court records show how he was able to use his experience in the political world and as a critical thinker to craft his mother’s defense. He used rigorous logic and research to dissect the testimony against Katharina, and rhetorical persuasion to argue her case.

The author does an excellent job of portraying Kepler as a multi-faceted individual and admits that he had a large collection of horoscopes and did chart interpretations and forecasts for his various patrons. But she unfortunately does not appear to have researched astrology, which could only have strengthened her work. Rublack provides an excellent historical context for Kepler’s “negative sketches,” but to an astrologer, these are obviously cook-book-like delineations of planetary combinations. She similarly states that “What we call ‘gender’ played no role at all in the explanatory framework of astrology,” which is simply incorrect. Interestingly, she shares some of Kepler’s unanswered questions about his own birth chart, which might be answered by using the outer planets today.

Rublack stresses Kepler’s skepticism, stating, “his view that astrology was of little value.” She is probably more correct in her later discussion, where she concludes that Kepler’s mature belief was non-deterministic, allowing for the influence of the human soul, culture, education, choice and habits to modify the horoscope: “good astrology was very much like medicine in its character, an inductive art, which required observation, experience and analysis.” Kepler’s beliefs were based upon his experience as well as his optimistic Christian world view; he also stressed the need for accurate birth data. Astrologically, he was an innovator, as he was in astronomy.

Despite my quibbles, this is an excellent book for anyone interested in the history of ideas, and particularly for astrologers who wish to learn more about one of their most successful forebears.

Buy on Amazon.com: The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother

Kepler’s Astrology, Ken Negus’ translation of some of Kepler’s astrological writings is available in print.

Culture & Cosmos’ edition on Kepler is unfortunately no longer available. See the Table of Contents here.